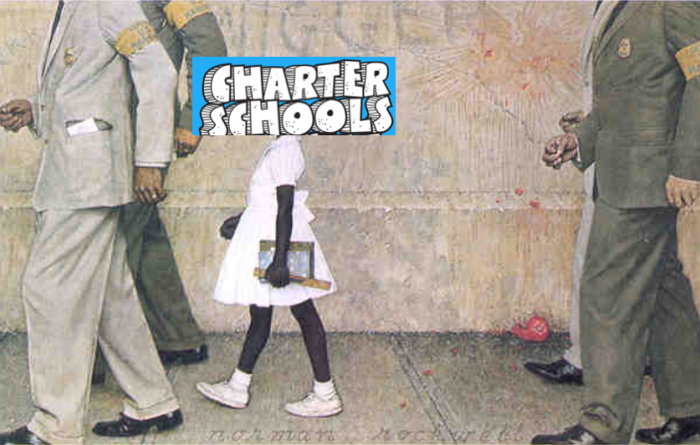

What’s More Important – Fighting School Segregation or Protecting Charter School Profits?

By Steven Singer, Director BATs Research/Blogging Committee

No one wants school segregation.

At least, no one champions it publicly.

As a matter of policy, it would be political suicide to say we need to divide up our school children by race and socio-economics.

But when you look at our public school system, this is exactly what you see. After thetriumphs of the Civil Rights movement, we’ve let our schools fall back into old habits that shouldn’t be acceptable in the post-Jim Crow era.

When we elected Barack Obama, our first President of color, many observers thought he’d address the issue. Instead we got continued silence from the Oval Office coupled with an education policy that frankly made matters worse.

So one wonders if people still care.

Is educational apartheid really acceptable in this day and age? Is it still important to fight against school segregation?

The former assistant Secretary of Education under Obama and prominent Democrat worries that fighting segregation may hurt an initiative he holds even more dear – charter schools.

Cunningham is executive director of the Education Post, a well-funded charter school public relations firm that packages its advertisements, propaganda and apologias as journalism.

Everywhere you look Democrats and Republicans are engaged in promoting various school choice schemes at the expense of the traditional public school system. Taxpayer money is funneled to private or religious schools, on the one hand, or privatized (and often for-profit) charter schools on the other.

One of the most heated debates about these schemes is whether dividing students up in this way – especially between privately run charter schools – makes them more segregated by race and socio-economic status.

Put simply – does it make segregation worse?

Civil Rights organizations like the NAACP and Black Lives Matter say it does. And there’s plenty of research to back them up.

But until recently, charter school apologists have contested these findings.

Cunningham breaks this mold by tacitly admitting that charter schools DO, in fact, increase segregation, but he questions whether that matters.

“Maybe the fight’s not worth it. It’s a good thing; we all think integration is good. But it’s been a long fight, we’ve had middling success. At the same time, we have lots and lots of schools filled with kids of one race, one background, that are doing great. It’s a good question.”

The schools he’s referring to are charter schools like the Knowledge is Power Program (KIPP) where mostly minority students are selected, but only those with the best grades and hardest work ethic. The children who are more difficult to teach are booted back to traditional public schools.

It’s a highly controversial model.

KIPP is famous for two things: draconian discipline and high attrition rates. Even those kids who do well there often don’t go on to graduate from college. Two thirds of KIPP students who passed the 8th grade still haven’t achieved a bachelor’s degree 10 years later.

Moreover, its methods aren’t reproducible elsewhere. The one time KIPP tried to take over an existing public school district and apply its approach without skimming the best and brightest off the top, it failed miserably – so much so that KIPP isn’t in the school turnaround business anymore.

These are the “lots and lots of schools” Cunningham is worried about disturbing if we tackle school segregation.

He first voiced this concern at a meeting with Democrats for Education Reform – a well-funded neoliberal organization bent on spreading school privatization. Even at such a gathering of like minds, some people might be embarrassed for saying such a thing. Is integration worth it? It sounds like something you’d expect to come out of Donald Trump’s mouth, not a supposedly prominent Democrat.

But Cunningham isn’t backing away from his remarks. He’s doubling down on them.

He even wrote an article published in US News and World Report called “Is Integration Necessary?”

Here’s the issue.

Segregation is bad.

But charter schools increase segregation.

So the obvious conclusion is that charter schools are bad.

BUT WE CAN’T DO THAT!

It would forever crash the gravy train that transforms public school budgets into private profits. It would forever kill the goose that turns Johnny’s school money intofancy trips, expense accounts and yachts for people like Cunningham.

This industry pays his salary. Of course he chooses it over the damage done by school segregation.

But the rest of us aren’t burdened by his bias.

His claims go counter to the entire history of the Civil Rights movement, the more than hundred year struggle for people of color to be treated equitably. That’s hard to ignore.

People didn’t march in the streets and submit to violent recriminations to gain something that just isn’t necessary. They weren’t sprayed by hoses and attacked by police dogs so they could gain an advantage for their children that isn’t essential to their rights. They weren’t beaten and murdered for an amenity at which their posterity should gaze with indifference and shrug.

We used to understand this. We used to know that allowing all the black kids to go to one school and all the white kids to go to another would also allow all the money to go to the white kids and the crumbs to fall to the black kids.

We knew it because that’s what happened. Before the landmark Brown vs. Board of Education, it’s a matter of historical fact. And today it’s an empirical one. As our schools have been allowed to fall back into segregation, resources have been allocated in increasingly unfair ways.

We have rich schools and poor schools. We have predominantly black schools and predominantly white schools. Where do you think the money goes?

But somehow Cunningham thinks charter schools will magically fix this problem.

Charters are so powerful they will somehow equalize school funding. Or maybe they’re so amazing they’ll make funding disparities irrelevant.

For believers, charter pedagogy wields just that kind of sorcery. Hocus Pocus and it won’t matter that black kids don’t have the books or extra-curriculars or arts and humanities or lower class sizes.

Unfortunately for Cunningham, the effects of school segregation have been studied for decades.

“Today, we know integration has a positive effect on almost every aspect of schooling that matters, and segregation the inverse,” says Derek Black, a professor of law at the University of South Carolina School of Law.

“We also know integration matters for all students. Both minorities and whites are disadvantaged by attending racially isolated schools, although in somewhat different ways.”

Minorities are harmed academically by being in segregated schools. Whites are harmed socially.

At predominantly minority schools, less money means less educational opportunities and less ability to maximize the opportunities that do exist. Likewise, at predominantly white schools, less exposure to minorities tends to make students more insular, xenophobic and, well, racist. If you don’t want little Billy and Sally to maybe one day become closeted Klan members, you may need to give them the opportunity to make some black friends. At very least they need to see black and brown people as people – not media stereotypes.

Even Richard D. Kahlenberg, a proponent of some types of charter schools and a senior fellow at the Century Foundation, thinks integration is vital to a successful school system.

“To my mind, it’s hugely significant,” says Kahlenberg, who has studied the impact of school segregation.

“If you think about the two fundamental purposes of public education, it’s to promote social mobility so that a child, no matter her circumstances, can, through a good education, go where her God-given talents would take her. The second purpose is to strengthen our democracy by creating intelligent and open-minded citizens, and related to that, to build social cohesion.Because we’re a nation where people come from all corners of the world, it’s important that the public schools be a place where children learn what it means to be an American, and learn the values of a democracy, one of which is that we’re all social equals. Segregation by race and by socioeconomic status significantly undercuts both of those goals.”

We used to know that public education wasn’t just about providing what’s best for one student. It was about providing the best for all students.

Public schools build the society of tomorrow. What kind of future are we trying to create? One where everyone looks out just for themselves or one where we succeed together as a single country, a unified people?

A system where everyone pays their own way through school and gets the best education they can afford works great for the rich. But it leaves the masses of humanity behind. It entrenches class and racial divides. In short, it’s not the kind of world where the majority of people would want their children to grow up.

More than half of public school students today live in poverty. Imagine if we could tap into that ever-expanding pool of humanity. How many more scientific breakthroughs, how many works of art, how much prosperity could we engender for everyone!?

That is the goal of integration – a better world.

But people like Cunningham only can see how it cuts into their individual bank accounts.

So is it important to fight school segregation?

That we’re even seriously asking the question tells more about the kind of society we live in today than anything else.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.