Originally published at: https://gadflyonthewallblog.com/2018/07/25/cyber-school-kingpin-gets-slap-on-wrist-for-embezzling-millions-from-pa-students/

Nick Trombetta stole millions of dollars from Pennsylvania’s children.

And he cheated the federal government out of hundreds of thousands in taxes.

Yet at Tuesday’s sentencing, he got little more than a slap on the wrist – a handful of years in jail and a few fines.

As CEO and founder of PA Cyber, the biggest virtual charter school network in the state, he funneled $8 million into his own pocket.

Instead of that money going to educate kids, he used it to buy a Florida condominium, sprawling real estate and even a private jet.

But it wasn’t enough.

He needed to support his extravagant lifestyle, buy a $933,000 condo in the Sunshine State, score a $300,000 twin jet plane, purchase $180,000 houses for his mother and girlfriend in Ohio, and horde a pile of cash.

What does a man like that deserve for stealing from the most vulnerable among us – kids just asking for an education?

At very least, you’d think the judge would throw the book at him.

But no.

Because he took a plea deal, he got a mere 20 months in federal prison.

That’s less than two years in jail for defrauding tens of thousands of students and multiple districts across the Commonwealth.

In addition, once he serves his time he’ll be on probation for 3 years.

And even though there is no mystery about the amount of money he defrauded from the Internal Revenue Service by shifting his income to the tax returns of others – $437,632, to be exact – the amount he’ll have to pay back in restitution is yet to be determined.

One would think that’s easy math. You stole $437,632, you need to pay back at least that amount – with interest!

And what of the $8 million? Though I can’t find a single explicit reference to what happened to it in the media, it is implied that the money was recovered and returned to Pa Cyber.

Yet there seems to be no discussion of a financial penalty for embezzling all that money. If my checking account dips below a certain balance, I’m penalized. If I don’t pay the minimum on my credit cards, I’m charged an additional fee. Yet this chucklehead pilfers $8 million and won’t be docked a dime!? Just paying it back is good enough!?

But what makes this sentence even more infuriating to me is the paltry jail time Trombetta will serve.

The judge actually gave him 17 months LESS than the minimum federal guidelines for this kind of case! He should at least be serving 37 to 46 months – 3 to 4 years!

Nonviolent drug charges often lead to sentences much longer than that!

For instance, in 2010, Kevin Smith was arrested for drug possession. He was locked up in a New Orleans jail for almost 8 years (2,832 days) without ever going to trial!

But then again, most of these nonviolent drug charges are against people of color. And Trombetta is white.

So is Neal Prence, a former certified accountant who pleaded guilty to helping Trombetta hide his ill-gotten gains.

Prence will serve a year and a day in prison and pay back $50,000 in restitution.

It’s a good thing he didn’t have any drugs on him.

And that he didn’t have a tan.

This is what we talk about when we talk about white privilege.

And speaking of that, compare this crime with the sentences given to the Atlanta teachers who were convicted of cheating on standardized tests a few years back.

These were mostly women and people of color.

They each got three years in prison, seven years probation, $10,000 in fines and 2,000 hours of community service.

So in America, cheating on standardized tests gets you a harder sentence than embezzling a fortune from school kids.

I’m not saying what the Atlanta teachers and administrators did was right, but their crime pales in comparison to Trombetta’s.

Think about it.

Atlanta city schools have suffered under decades of financial neglect. The kids – many of whom are students of color – receive fewer resources, have more narrowed curriculum and are forced to live under the yoke of generational poverty.

Yet their teachers were told to increase test scores with little to no help, and if they didn’t, they’d be fired.

I can’t imagine why they tried to cheat a system as fair as that.

It’s like being mugged at gunpoint and then the judge convicts you of giving your robber a wooden nickel.

The worst part of all of this is that we haven’t learned anything from either case.

High stakes standardized testing has become entrenched in our public schools by the newly passed federal law – the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA).

And though Trombetta resigned from his post as CEO of PA Cyber in September 2013, cyber charters are as popular as ever.

These are publicly funded but privately run schools that provide all or most instruction on-line. Think Trump University for tweens and teenagers.

You can’t turn on the TV without a commercial for a cyber charter school showing up. You can’t drive through a poor neighborhood without a billboard advertising a virtual charter. They even have ads on the buggies at the grocery store!

Yet these schools have a demonstrated track record of failure even when compared to brick-and-mortar charter schools. And when you compare them to traditional public schools, it’s like comparing a piece of chewed up gum on the bottom of your shoe to a prime cut of filet mignon.

A 2016 study found that cyber charters provide 180 days less of math instruction than traditional public schools.

Keep in mind there are only 180 days of school in Pennsylvania!

That means cyber charters provide less math instruction than not going to school at all.

When it comes to reading, the same study found cyber charters provide 72 days less instruction than traditional public schools.

That’s like skipping 40% of the school year!

And this isn’t just at one or two cyber charters. Researchers noted that 88 percent of cyber charter schools produce weaker academic growth than similar brick and mortar schools.

They concluded that these schools have an “overwhelming negative impact” on students.

AND THAT’S ALL LEGAL!

In Pennsylvania, nearly 35,100 of the 1.7 million children attending public schools are enrolled in cyber-charter schools. With more than 11,000 students, PA Cyber is by far the largest of the state’s 16 such schools.

If Trombetta had just stiffed Pennsylvania’s students that much, he wouldn’t have been in any trouble with the law.

However, he got even greedier than that!

He needed more, More, MORE!

Justice – such as it is in this case – was a long time coming.

Trombetta was first indicted back in 2013 – five years ago.

He was facing 11 counts of mail fraud, theft or bribery, conspiracy and tax offenses related to his involvement in entities that did business with Pa. Cyber. He pleaded guilty to tax conspiracy almost two years ago, acknowledging that he siphoned off $8 million from The Pennsylvania Cyber Charter School.

He has been free on bond all this time.

His sister, Elaine Trombetta, agreed to cooperate with prosecution, according to federal court filings. She pleaded guilty in October 2013 to filing a false individual income tax return on her brother’s behalf and has yet to be sentenced.

It was only yesterday that her brother – the kingpin of this conspiracy – was ultimately sentenced.

Finally, he’ll have to face up to what he did.

Finally, he’ll have to pay for what he’s done.

Just don’t blink or you’ll miss it.

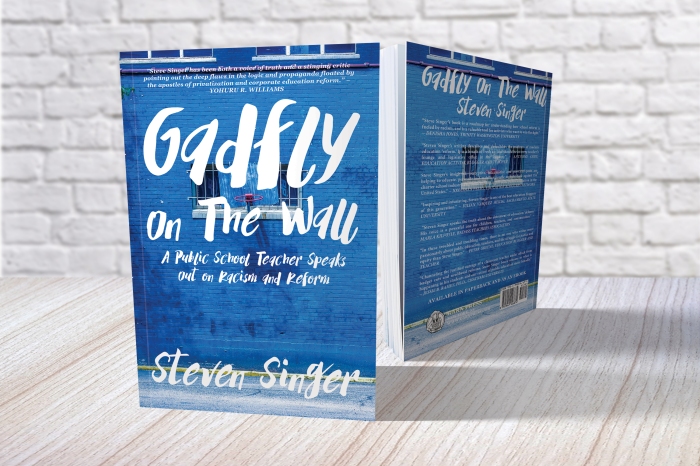

Like this post? I’ve written a book, “Gadfly on the Wall: A Public School Teacher Speaks Out on Racism and Reform,” now available from Garn Press. Ten percent of the proceeds go to the Badass Teachers Association. Check it out!

WANT A SIGNED COPY?