Andrea Gabor has written another outstanding book. This latest is titled After the Education Wars. In it, she makes a radical departure from the top-down models of education reform that have dominated the last two decades. Gabor, a Bloomberg chair of business journalism, has applied her expertise toward analyzing modern education policy. Through five case studies she convincingly argues that business leaders brought the wrong lessons to education when they imposed Fredrick Winslow Taylor’s scientific management and shunned William Edwards Deming’s continuous improvement.

Taylor was a mechanical engineer who became intrigued by the problem of efficiency at work. He is widely viewed as inventing industrial engineering; his 1911 Principles of Scientific Management became the most influential book on American management practices during the twentieth century. In it he wrote,

It is only through enforced standardization of methods, enforced adoption of the best implements and working conditions, and enforced cooperation that this faster work can be assured. And the duty of enforcing the adoption of standards and enforcing this cooperation rests with management alone.

Taylor was strongly anti-union. He saw them as wastefully introducing inefficiencies into the work place.

Andrea Gabor’s first book The Man Who Discovered Quality was about William Edwards Deming. That book was reviewed by Business Week in 1991. Some key statements in the review:

A trio of reverential new books celebrates Deming’s management principles. In Deming Management at Work, Mary Walton, a writer for The Philadelphia Inquirer Magazine, focuses on how six organizations, including the U. S. Navy, have applied his methods. You get much of the same from both Rafael Aguayo’s Dr. Deming: The American Who Taught the Japanese About Quality and Andrea Gabor ‘s The Man Who Discovered Quality, even though their titles suggest biographical accounts. Aguayo, a former bank executive, essentially offers a schematic for putting Deming’s teachings to work.

Gabor, formerly a staff editor for this magazine and now a senior editor at U. S. News & World Report, provides far more insight into the man, which makes hers the most accessible and enjoyable of the three books. Born in Iowa, Deming grew up in a tarpaper shack in Wyoming. He earned a scholarship to Yale University, where he graduated in 1928 with a PhD in mathematical physics. He worked for the Agriculture Dept. and then the U. S. Census Bureau before the War Dept. sent him to Japan in the late 1940s to help rebuild that war-torn nation. Gabor vividly describes Deming’s early visits, using his personal diary to bring to life his rise to prominence.

The Business Week review ended with,

“How great is Deming’s influence in Japan? On the walls in the main lobby of Toyota’s headquarters in Tokyo, three portraits hang. There is one of the founder and one of the current chairman. But Deming’s is the largest of all.”

In 1979, Ford would lose a billion dollars and General Motors would lose a whopping 2.5 billion dollars. Many people blamed President Jimmy Carter. Industry leaders blamed unions and lazy workers. When out of desperation they called on Deming, he blamed management.

In the forward to her new book, Gabor highlights two key points of Deming’s teaching:

“Ordinary employees – not senior management or hired consultants – are in the best position to see the cause-and-effect relationships in each process …. The challenge for management is to tap into that knowledge on a consistent basis and make the knowledge actionable.”

“More controversially, Deming argued, management must also shake up the hierarchy (if not eliminate it entirely), drive fear out of the workplace, and foster intrinsic motivation if it is to make the most of employee potential.”

The Bush-Kennedy No Child Left Behind (NCLB) legislation with its test and punishment philosophy of education improvement was a clear violation of Deming’s core principles. Today, NCLB is widely seen as a damaging failure. Obama’s Race to the Top (RTTT) had a school “turn-around” strategy of hiring consultants or charter management organizations to fix schools that didn’t reach testing benchmarks. It was a consistent failure because they did not understand the cause and effect relationships starting with their completely incapable testing instrument for measuring failure.

Instead of removing fear from teacher ranks, NCLB and RTTT injected more fear into them. I am one teacher who will never forget the President of the United States congratulating the Central Falls, Rhode Island school board for firing all 88 teachers at Central Falls High School because the test scores were too low.

NCLB and RTTT were bad policy based on bad ideology. They embraced Taylorism and ignored Deming. However, there are wonderfully successful examples of schools and even states embracing Deming style continuous improvement through bottom up leadership. Gabor’s deeply researched book shares a few of their stories which demonstrate success in education leadership.

The Small School Progressives

The progressive education grassroots movement appears to have gotten its inspiration from Britain’s 1960’s open-education which had intellectual roots going back to Friedrich Froebel, John Dewey and Jean Piaget. Lillian Weber, a City College professor who studied in England brought open-education to the attention of New York’s reformers. That is where Deborah Meier became her star mentee. Sixties student activists Ann Cook and Herb Mack traveled to London in the 1960’s to observe open-education first hand. They became small school advocates consistent with Gabor’s description of the progressive leaders as “for the most part, anti-establishment ‘lefty hippies’…”

Gabor observed that surprisingly, these progressives ran schools that were lean, entrepreneurial and efficient.

One antidote from Gabor shows the stark difference between schools envisioned by the New York progressives and today’s no-excuses charter school leaders:

“As Meier, a protégé of Weber, explained it, the hallways and lobbies of schools ‘work best if we think of them as the marketplaces in small communities – where gossip is exchanged, work displayed, birthdays taken note of; where clusters of kids and adults gather to talk, read and exchange ideas.’”

In 1973, Tony Alvarado was named Superintendent of District 4 in New York City which is in a poor largely black and Latino neighborhood. Alvarado fostered an educator driven approach to school improvement. He encouraged educators to start new schools and schools within a school. Gabor notes, “Put simply, Alvarado was a master at fostering both improvements from grassroots up and creative non-compliance.”

In 1974, he heard about Deborah Meier and together they launched Central Park East which brought open-education to District 4. This was the first of what would eventually run into the hundreds of these small progressive schools across New York City. When Alvarado arrived, district four had the lowest reading score among the cities 32 districts. In ten years, it climbed to fifteenth.

Alvarado went to District 2 in 1988. It was ranked near the middle of the cities districts and in a decade it was ranked number 2.

Another important factor in the success of the New York Progressives was the support of Ted Sizer’s Coalition of Essential Schools. As the small school movement progressed, Sizer’s organization and Meier’s Center for Collaborative Education provided important infrastructure such as training, funding and political support. The pedagogic emphasis was on learning depth over quantity which is one of the stated goals of the now loathed top down imposed common core state standards.

I cannot do justice to Andrea’s well written readable and engaging account of the New York’s small school progressives. However, I wanted to share this much because I have a personal experience with two of the protagonists of this story; Tony Alvarado and Deborah Meier.

Chapter four in Diane Ravitch’s startling change of view book The Death and Life of the Great American School System tells the story of the unlikely school reform effort in San Diego, California. A non-educator and politically connected former federal prosecutor, Alan Bersin, was named Superintendent of Schools in 1998. He was given carte blanche powers to reform the district. Ravitch noted that San Diego was an unlikely place to launch a reform movement because it was seen as “one of the nation’s most successful urban school districts.”

Bersin was a Harvard man so he went to Harvard for direction and that is where he heard about District 2 in New York City and Anthony Alvarado. Bersin brought Alvarado to San Diego to be in charge of the education agenda while he took care of the politics.

For some reason, Alvarado completely abandoned his “grassroots up and creative non-compliance” that had led to such success in New York. In 1999, two-thousand teachers demonstrated at a San Diego Unified School District board meeting to protest the administration’s top-down mandates. Ravitch reported that the Bersin-Alvarado management employed “centralized decision making and made no pretense of collaborating with teachers.”

In 2002, my first teaching job was working under Bersin-Alvarado. It was a miserable experience characterized by fear and loathing everywhere. It seemed that besides the no-input mandates, there was a quota on number of teachers to be fired. The belief among teachers was a certain number teachers were to be fired as an example for the rest.

I was a fifty-one year-old first year educator teaching five sections of physics to ninth-graders at Bell Junior High School, a poor, non-white and low scoring school. My classes actually did well on the end of course exams including my honors class being the second highest scoring in a large district with many wealthy communities.

I was evaluated as “not moving my students to achieving standards.” A designation that meant I could not even apply to be a substitute teacher.

In 2015, I was able to spend an hour talking with Deborah Meier and her niece from Denver. Both of them were discouraged by the turn events in public education. Especially the niece from Denver was seeing little hope for the future of America’s public schools. Later, I investigated the destruction of Denver’s public education and I understand why she was so down.

I asked Deborah “what happened to your friend Tony Alvarado when he came to San Diego.” She had no explanation why he abandoned the model of teacher led continuous improvement after his own twenty-five year history of successfully applying it.

Deborah had been a larger than life figure to me for a few decades. When I had the opportunity to speak with her, I was so happy to discover that she is just as warm and humble as she is brilliant.

A Tale of Two States: Michigan and Massachusetts

Brockton, Massachusetts the birthplace of Rocky Marciano and Marvin Hagler is home to Brockton High School (BHS) famous for its athletics. By 1993, BHS became a rallying cry for school reform in the state. Even Republican Governor William Weld’s own commission agreed that BHS was not funded properly.

Gabor takes the reader through the motivation for Massachusetts’ education reform and its bottom up development. She notes there was broad-based leadership from the governor, from business, from legislators, from the judiciary, from teachers and their unions. They created “a clear vision of what education reform should look like.”

There was a “grand bargain” to increase spending in exchange for increased accountability. A “collaborative, transparent, and iterative approach to developing both a new curriculum and a standardized test that became the graduation requirement” was carried out. Gabor writes, “… Massachusetts reforms grew out of a deliberate, often messy and deeply democratic process…”

Much of the story of the Massachusetts reform is told through the transformation of the giant 4,000 plus students BHS. It was the story of home grown reform led by locals who themselves attend BHS. They proved a large school can succeed. Gabor shares,

“Within a little over a decade, Brockton would go from one of the lowest performing schools in the state to one of the highest and, in 2009, it would be featured in a Harvard University report on exemplary schools that have narrowed the minority achievement gap. Today, 85 percent of Brockton students score advanced or proficient on the MCAS, the state’s standardized tests, and 64 percent score advanced or proficient in math.”

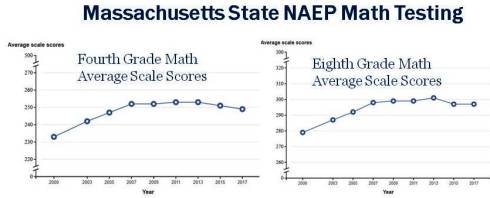

In 2010, Massachusetts abandoned parts of their successful education reform agenda in order to win a $250 million dollar RTTT grant. They abandoned their state standards and curriculum to adopt the Common Core State Standards. The result looks bad. It seems that after more than a decade of continuous improvement, progress has slowed or possibly reversed as suggested by National Assessment of Education Progress (NAEP) data.

Graphs Created Using the NAEP Data Explorer

In the late 1990’s, Michigan and Massachusetts chose opposite paths of education reform. Michigan embraced school choice while Massachusetts rejected it. Massachusetts increased school spending. Michigan did not. Michigan imposed school reform in a top-down fashion with little educator input. Massachusetts embraced educator contributions to education reform. Eighth grade math NAEP results provide stunning evidence for which choices were better.

The Nations Report Card Provided the Data

Conclusions

Gabor found a school district in Texas that embraced Deming’s quality ideas thirty-five years ago. Leander school district is non-urban and is in a right to work state in the middle of a mostly white Christian and Republican community. I find this all important, because it shows that the continuous improvement model led by educators, students and parents works in any political environment. It is not a red state – blue state or union dependent thing. It shows Deming’s leadership principles are sound and perhaps universal.

I met Andrea Gabor in Raleigh, North Carolina at the Network for Public Education conference of April, 2016. She had come there from New Orleans accompanied by friends she made there while researching this book. For a guy like me who grew up in rural mostly white Idaho and then moved to pluralistic California to serve in the integrated US Navy, the story of profound and continuous racism in New Orleans were beyond my ability to apprehend. There was a conscious centuries long effort made there to limit education among the black population!

When all of the black professional educators in New Orleans were fired after hurricane Katrina and replaced with mostly white college graduates from Teach for America, it was a continuation of that same centuries of racial injustice.

In Raleigh, Andrea made it clear that she was not anti-charter school and in her book she presents the story of one particularly successful school, Morris Jeff, that exemplified the Deming approach. Morris Jeff is one of the few mixed race schools in New Orleans and their students are outperforming the cities “no-excuses” charters.

Bottom line, this is a special book and I encourage you to read it. It’s ideas are both thought provoking and promising.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.