In 1997, New York University professor, Lawrence M. Mead, edited a book entitled“The New Paternalism: Supervisory Approaches to Poverty.” Mead’s work, spanning more than 30 years, has been highly influential in the implementation of draconian and ineffective work requirements for government assistance programs. “The New Paternalism” directly inspired noted education reformer, David Whitman, to write the award-winning “Sweating the Small Stuff: Inner City Schools and the New Paternalism” in 2008. Whitman writes,

“The schools profiled in this book are paternalistic in the very way described by Mead. They unapologetically tell children continually what is good for them. They also compel good behavior and keep adolescents off the wrong track using both carrots and sticks. The students who attend them are closely supervised in an effort to change their behavior and create new habits, and maybe even new attitudes.”

And later,

“The paternalistic presumption, implicit in the schools portrayed here, is that the poor lack the family and community support, cultural capital, and personal follow-through to live according to the middle-class values that they, too, espouse.”

Whitman’s work has contributed to a continuing legacy of discriminatory admissions policies, racist dress codes, and systemic resegregation at “no excuses” charter schools.

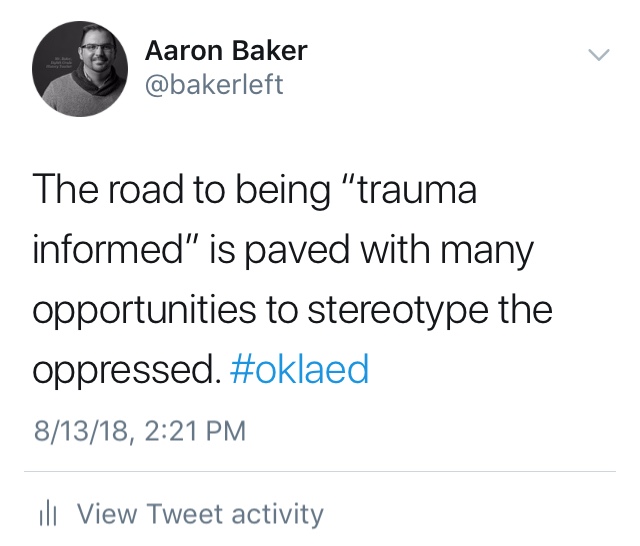

The problems with paternalistic models of education are innumerable. Particularly notable among them is the way that paternalism epitomizes institutional racism and directly feeds the school-to-prison pipeline. It is doubtful that many educators today are comfortable with Whitman’s language. Education reformers today are considerably less brash when choosing words to describe their “white savior” philosophies of education. The truth is there is absolutely no place for paternalism in public schools. Blatant paternalism manifests explicit biases. The complete eradication of paternalism is necessary for addressing what are called “implicit biases.” The subtle ways that educators act on these implicit biases are called “microaggressions.” Addressing specific examples of teacher microaggressions does not come without controversy (“’Take Your Hood Off’ and Other Teacher Microaggressions”).

As the overtly oppressive nature of the new paternalism became more and more obvious, the education reform movement began looking for other methodologies that more effectively concealed attempts to teach students to, in Whitman’s words, “act according to what are commonly termed traditional, middle-class values.” Most education reformers are moving away from “zero tolerance” models of discipline, but are still very much interested in pedagogies that involve educators “fixing” students. Enter “trauma informed schools.”

The two fold assertion of trauma informed schools is that 1. Students have trauma that they bring to school every day and 2. Educators can be equipped to teach students how to deal with that trauma. The first assertion supports the needed expansion of the community school model and a “whole child” approach to education and is in line with important and welcomed changes to school discipline strategies like restorative justice.Being “trauma informed” is not the problem with trauma informed schools. Knowledge of student trauma should absolutely transform and expand our models of “wrap around” services, our approach to discipline, our concept of classroom management, our school practices related to food, and even our policies concerning students leaving the classroom for bathroom and water breaks.

Most education reformers are moving away from “zero tolerance” models of discipline, but are still very much interested in pedagogies that involve educators “fixing” students.

The paternalism of trauma informed schools lies in the second assertion; that educators can be equipped to teach students how to modify the behavior resulting from the trauma they have experienced. Both models of paternalism, Whitman’s standardized heavy handed approach and the personalized and sensitive nature of trauma informed schools, are examples of what Paulo Freire called the “banking” approach to education. Although trauma informed schools recognize that students arrive at school with their “accounts” prefilled with their own experiences, the focus is still on the ability of the teacher to make “deposits” into those accounts. In his seminal work, “Pedagogy of the Oppressed,” Freire says that this kind of approach to education is dehumanizing and only reinforces society’s preexisting oppressive attitudes.

At the height of popularity, previous paternalistic models of education made high claims of being able to close the “achievement gap” and touted the virtues of teaching “grit.” As a learnable skill, grit has been effectively debunked by The Washington Postand Slate, and yet news of schools including “processing skills” into their grading system continue to emerge. Now, the language of trauma informed schools has shifted toward an understanding of “adverse childhood experiences” and the teaching of “resilience.” Same conversation, different words. This piece by David Webster and Nicola Rivers, “Critiquing Discourses of Resilience in Education,” is at the forefront of the critique of teaching resilience, especially in higher education. The pressure upon students to be resilient seems to increase as the academic rigor naturally increases in high school and particularly at the college and university level.

Not all trauma is equal. That’s what makes teaching resilience so problematic. I cannot empathize with a student experiencing trauma associated with incarceration. Therefore, I cannot teach said student to be resilient in the face of that trauma. Despite a steady decline in respect for the teaching profession, as reflected by the recent wave of teacher walkouts, education is still a rather privileged vocation. Of course, teachers have their own trauma, but the emerging trauma informed school trope is of a teacher with an ACE score of maybe 1 or 2 in a classroom full of students with ACE scores of 7 or higher. Simply put, it is paternalistic for this teacher to attempt to teach these students grit, resilience, self-regulation, delayed gratification, or anything similar.

There are certain “soft skills” that everyone needs, students and teachers alike, regardless of ACE score. Mindfulness, active listening, breathing techniques, conflict resolution, nonviolent communication, and even skills like cooking and gardening are all essential to whole child approaches to education. There is no need to attach these practices specifically to some perceived deficit found in students who have difficult life circumstances. The goal is not to be trauma ignorant. The goal is to ensure that our practices don’t reinforce the idea that people experience poverty related trauma through some fault of their own.

What is most concerning about the shift toward trauma informed schools is what is not included. Proponents of trauma informed schools like to say that it is not about socioeconomic status and that everyone has trauma regardless of identities like class and race. This line of reasoning is a red herring. To suggest that trauma resulting from incarcerated relatives, substance abuse, or emotional neglect, for example, is not experienced at higher levels among oppressed classes and races is itself oppressive. Similar to the work of Ruby Payne, a shift toward trauma informed schools does not include the important contributions of critical race theory or a critique of the oppressive nature of capitalism.

Schools, community partners, and social service organizations have the opportunity to cooperatively transform the systems that create the occasions for trauma. The appropriate response to trauma is to tear down systems of oppression, not to teach coping skills. The last thing students with high levels of adverse childhood experiences need is self-regulation. What high ACE students need is a robust education in class warfare and the opportunity to take back their power from their oppressors. Schools must look beyond merely being “trauma informed” to being “trauma transforming.”

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.