Whiteness: The Lie Made True

By Steven Singer, Director of BATs Blogging and Research Committee

“The discovery of a personal whiteness among the world’s peoples is a very modern thing,—a nineteenth and twentieth century matter, indeed.” – W. E. B. Du Bois

What color is your skin?

You don’t have to look. You know. It’s a bedrock fact of your existence like your name, religion or nationality.

But go ahead and take a look. Hold out your hand and take a good, long stare.

What do you see?

White? Black? Brown?

More than likely, you don’t see any of those colors.

You see some gradation, a hue somewhere in the middle, but in the back of your mind you label it black, white, brown, etc.

When I look, I see light peach with splotches of pink. But I know that I’m white, White, WHITE.

So where did this idea come from? If my skin isn’t actually white – it’s not the same white I’d find in a tube of paint, or on a piece of paper – why am I labeled white?

The answer isn’t scientific, cultural or economic.

It’s legal.

Yes, here in America we have a legal definition of whiteness.

It developed over time, but the earliest mention in our laws comes from theNaturalization Act of 1790.

Only 14 years after our Declaration of Independence proclaimed all people were created equal, we passed this law to define who exactly has the right to call him-or-herself an American citizen. It restricted citizenship to persons who resided in the United States for two years, who could establish their good character in court, and who were white – whatever that meant.

In 1896 this idea gained even more strength in the infamous U.S. Supreme Court decision Plessy v Ferguson. The case is known for setting the legal precedent justifying segregation as “separate but equal.” However, the particulars of the case revolve around the definition of whiteness.

Homer Plessy was kicked off the white section of a train car, and he sued – not because he thought there was anything wrong with segregation, but because he claimed he was actually white. The U.S. Supreme Court was asked to define what that means.

Notably the court took this charge very seriously, admitting how important it is to be able to distinguish between white and non-white. Justices claimed whiteness as a kind of property – very valuable property – the denial of which could incur legal sanction.

In it’s decision, the court said, “if he be a white man, and be assigned to the color coach, he may have his action for damages from the company, for being deprived of his so-called property. If he be a colored man and be so assigned, he has been deprived of no property, since he is not lawfully entitled to the reputation of being a white man.”

Plessy wasn’t the only one to seek legal action over this. Native Americans were going to court claiming that they, too, were white and should be treated as such. Much has been written about the struggle of various ethnic groups – Irish, Slovak, Polish, etc. – to be accepted under this term. No matter how you define it, most groups wanted it to include them and theirs.

However, it wasn’t until 1921 when a strong definition of white was written in the “Emergency Quota and Immigration Acts.” It states:

“A White person has been held to include an Armenian born in Asiatic Turkey, a person of but one-sixteenth Indian blood, and a Syrian, but not to include Afghans, American Indians, Chinese, Filipinos, Hawaiians, Hindus, Japanese, Koreans, negroes; nor does white person include a person having one fourth of African blood, a person in whom Malay blood predominates, a person whose father was a German and whose mother was a Japanese, a person whose father was a white Canadian and whose mother was an Indian woman, or a person whose mother was a Chinese and whose father was the son of a Portuguese father and a Chinese mother.”

So there you have it – whiteness – legally defined and enforceable as a property value.

It’s not a character trait. It’s certainly not a product of the color wheel. It’s a legal definition, something we made up. THIS is the norm. THAT is not.

Admitting that leads to the temptation to disregard whiteness, to deny its hold on society. But doing so would be to ignore an important facet of the social order. AsBrian Jones writes, the artificiality of whiteness doesn’t make it any less real:

“It’s very real. It’s real in the same way that Wednesday is real. But it’s also made up in the same way that Wednesday is made up.”

You couldn’t go around saying, “I don’t believe in Wednesdays.” You wouldn’t be able to function in society. You could try to change the name, you could try to change the way we conceptualize the week, but you couldn’t ignore the way it is now.

And whiteness is still a prominent feature of America’s social structure.

Think about it. A range of skin colors have become the dominant identifier here in America. We don’t like to talk about it, but the shade of your epidermis still means an awful lot.

It often determines the ease with which you can get a good job, a bank loan or buy a house in a prosperous neighborhood. It determines the ease with which you can go to a well-resourced school, a district democratically controlled by the community and your access to advanced placement classes. And it determines the degree of safety you have when being confronted by the police.

But to have whiteness as a signifier of the good, the privileged, we must imply an opposite. It’s not a term disassociated from others. Whiteness implies blackness.

It’s no accident. Just as the concept of whiteness was invented to give certain people an advantage, the concept of blackness was invented to subjugate others. However, this idea goes back a bit further. We had a delineated idea of blackness long before we legalized its opposite.

The concept of blackness began in the Virginia colonies in the 1600s. European settlers were looking to get rich quick through growing tobacco. But that’s a labor-intensive process and before mechanization it frankly cost too much in salaries for landowners to make enough of a profit to ensure great wealth. Moreover, settlers weren’t looking to grow a modest amount of tobacco for use only in the colonies. They wanted to produce enough to supply the global market. That required mass production and a disregard for humanity.

So tobacco planters decided to reduce labor costs through slavery. They tried enslaving the indigenous population, but Native Americans knew the land too well and would escape quicker than they could be replaced.

Planters also tried using indentured servants – people who defaulted on their debts and had to sell themselves into slavery for a limited time. However, this caused a lot of bad feeling in communities. When husbands, sons and relations were forced into servitude while their friends and neighbors remained free, bosses faced social and economic recriminations from the general population. Moreover, when an indentured servant’s time was up, if he could raise the capital, he now had all the knowledge and experience to start his own tobacco plantation and compete with his former boss.

No. planters needed a more permanent solution. That’s where the idea came from to kidnap Africans and bring them to Virginia as slaves. This was generational servitude, no time limits, no competition, low cost.

It’s important to note that it took time for this kind of slavery to take root in the colonies. Part of this is due to various ideas about the nature of Africans. People at the time didn’t all have our modern prejudices. Also it took time for the price of importing human beings from another continent to became less than that of buying indentured servants.

The turning point was Bacon’s Rebellion in 1676. Hundreds of slaves and indentured servants came together and deposed the governor of Virginia, burned down plantations and defended themselves against planter militias for months afterwards. The significance of this event was not lost on the landowners of the time. What we now call “white” people and “black” people had banded together against the landowners. If things like this were to become more frequent, the tobacco industry would be ruined, or at very least much less profitable for the planters.

After the rebellion was put down, the landed gentry had to find a way to stop such large groups of people from ever joining in common cause again. The answer was the racial caste system we experience today.

The exact meaning of “white” and “black” (or “colored”) was mostly implied, but each group’s social mobility was rigidly defined for the first time. Laws were put in place to categorize people and provide benefits for some and deprivations for others. So white people were then allowed to own property, own guns, participate in juries, serve on militias, and do all kinds of things that were to be forever off-limits to black people. It’s important to understand that black people were not systematically barred from these things before.

Just imagine how effective this arrangement was. It gave white people a permanent,unearned social position above black people. No matter how hard things could get for impoverished whites, they could never sink below this level. They would always enjoy these privileges and by extension enjoy the deprivation of blacks as proof of their own white superiority. Not only did it stop whites from joining together with blacks in common cause, it gave whites a reason to support the status quo. Sound familiar? It should.

However, for black people the arrangement was devastating.

As Brian Jones puts it:

“For the first time in human history, the color of one’s skin had a political significance. It never had a political significance before. Now there was a reason to assign a political significance to dark skin — it’s an ingenious way to brand someone as a slave. It’s a brand that they can never wash off, that they can never erase, that they can never run away from. There’s no way out. That’s the ingeniousness of using skin color as a mark of degradation, as a mark of slavery.”

All that based on pigmentation.

Our political and social institutions have made this difference in appearance paramount in the social structure, but what causes it? What is the essential difference between white people and black people and can it in any way justify these social distinctions, privileges and deprivations?

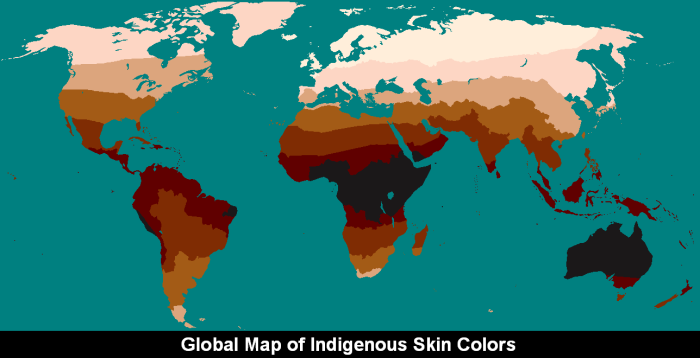

Science tells us why human skin comes in different shades. It’s based on the amount of melanin we possess, a pigment that not only gives color but blocks the body from absorbing harmful ultraviolet radiation from the sun. Everyone has some melanin. Fair skinned people can even temporarily increase the amount they have by additional solar exposure – tanning.

If the body absorbs too many UV rays, it can cause cancers or produce birth defects in the next generation. That’s why groups of people who historically lived closer to the equator possess more melanin than those further from it. This provided an evolutionary advantage.

However, the human body needs vitamin D, which often comes from sunlight. Having a greater degree of melanin can stop the body from absorbing the necessary Vitamin D and – if another source isn’t found -health problems like Sickle-cell anemia can occur.

That’s why people living further from the equator developed lighter skin over time. Humanity originated in Africa, but as peoples migrated north they didn’t need the extra melanin since they received less direct sunlight. Likewise, they benefited from less melanin and therefore easier absorption of Vitamin D from the sunlight they did receive.

That’s the major difference between people of different colors.

Contrary to the persistent beliefs of many Americans, skin color doesn’t determine work ethic, intelligence, honesty, strength, or any other character trait.

In the 19th through the 20th Centuries, we created a whole field of science called eugenics to prove otherwise. We tried to show that each race had dominant traits and some races were better than others.

However, modern science has disproven every scrap of it. Eugenics is now considered a pseudoscience. Everywhere in public we loudly proclaim that judgments like these based on race are unacceptable. Yet the pattern of positive consequences for light skinned people and negative consequences for dark skinned people persists. And few of us want to identify, discuss or – God forbid – confront it.

And that’s where we are today.

We in America live in a society that still subscribes to the essentially nonsensical definitions of the past. Both white and black people have been kept in their place because of them.

In each socio-economic bracket people have common cause that goes beyond skin color. But the ruling class has used a racial caste system to stop us from joining together against them.

This is obvious to most black people because they deal with the negative consequences of it every day. White people, however, are constantly bombarded by tiny benefits without noticing they’re present at all. White people take it as their due – this is what all people deserve. And, yes, it IS what all people deserve, but it is not what all people are receiving!

We are faced with a difficult task. We must somehow both understand that our ideas about race are man-made while taking arms against them. We must accept that whiteness and blackness are bogus terms and yet they dramatically affect our lives. We must preserve all that makes us who we are while fighting for the common humanity of all.

And we can’t do that by simply ignoring skin color. That kind of colorblindness only helps perpetuate the status quo. Instead, we must pay attention to inequalities based on the racial divide and actively work to counteract them.

In short, there are no white people and black people. There are only racists and anti-racists.

Which will you be?

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.